I went to see Ed Sheeran live the other day.

I can assure that’s not a sentence I thought I would be writing. At the start of his meteoritic rise, I couldn’t hear Shape of You one more time. Then my daughter got into him, which meant pretty much having the Divide album on loop.

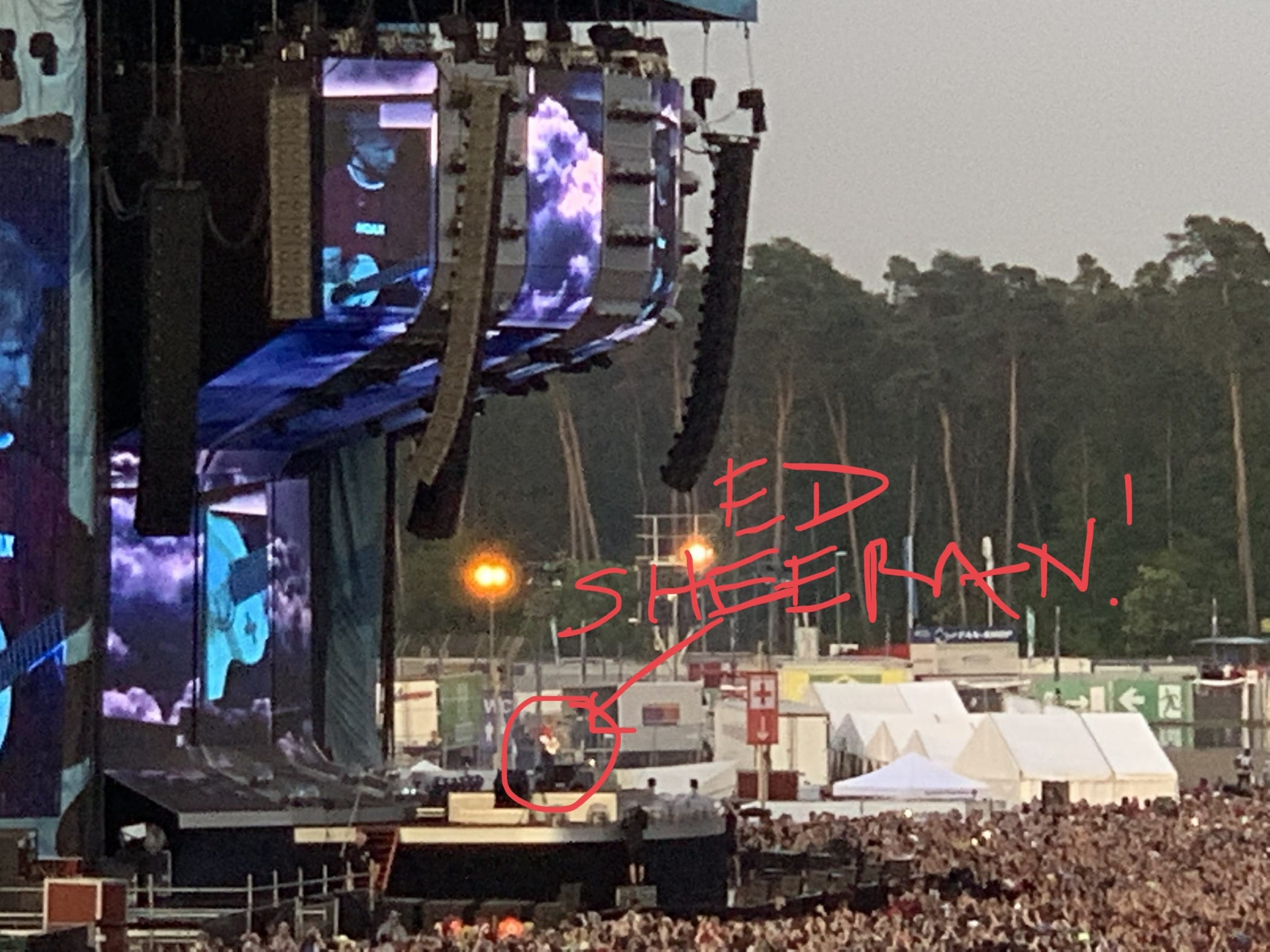

The repetition made me appreciate the songwriting a bit more and led to watching a few performances on YouTube and that led to us treating our 10 year-old to her first big concert. And big it was. Sheeran’s performance at the Hockenheimring in Germany was, according to him on the night, the biggest crowd he had ever played to at nearly 100,000 people. We booked late and were at seats about 12 miles away from the stage at the edge (children aren’t allowed in the standing area anyway), but that didn’t matter. His performance was remarkable — just him, his guitar and mic, and a Loop Station. He uses the Loop Station to record loops and build up the track live, accompanying himself. All for two hours.

Now, I’ve done some live performance with loops (really, don’t click that link) and I know full well how quickly that can go awry. You only have to get the timing a tiny bit off and you’ve got cross-beats and a musical mess. Gary Dunne, who taught Sheeran how to use loop pedals, explained and defended the art recently saying, ”I find it interesting that people can watch the gig and criticise the art and not understand the complexity and the vulnerability of what he’s doing.” The level of practice and musicianship is impressive, especially in the days of giant spectacle performances of the Lady Gaga ilk.

Newly impressed by Ed Sheeran, I watched the documentary about him called Songwriter, made by his cousin Murray Cummings. It documents the process of him writing the Divide album, from first glimpse of song ideas through to the finished album.

There are several musicians in his circle who seem to be trying very hard to look like pop-stars, but Sheeran remains remarkably down-to-earth. What really struck me was the importance of a psychologically safe and focused environment for the process, and how portable digital audio recording tools have transformed it.

Now that design has been so democratised and the mantra of “everyone is a designer” underpins the rise (and fall?) of design thinking, the craft skill is often overlooked. This isn’t so with music (well, maybe with DJs who record their sets on USB and hit play on the night). Playing an instrument and songwriting are still viewed with the awe of, “I couldn’t do that” by many buying into the talent myth. This has allowed musicians to make a clearer argument for “special” ways of working to maintain the “magic.”

Sheeran writes and records in a variety of sessions, but one part of the documentary shows them at the house in the country of producer, Benny Blanco. This allows them immense focus, away from the record label suits and any other distractions. It also creates the psychologically safe space for the songs to emerge, fragile and half formed, and then evolve.

The documentary starts with Sheeran recording parts of new song ideas in the back of his tour bus with Benny. Benny is afraid of flying, so they cross the Atlantic on a cruise ship and there is a section where they’re recording and producing in a pop-up studio they’ve created in some back room of the ship. It’s quite remarkable that any of this is possible when you think of how much kit recording studios used to require. Non-linear digital editing also means he can record the bits of the song he’s happy with—a kind of musical MVP—and drop in lines later, once he has them until it’s complete.

Galway Girl, for example, starts with a few chords and a couple of lines (“She played the guitar with an Irish band, dancing slow with an Englishman…” - the final lyrics are different) and lots of humming for the bits that he hasn’t thought of words for yet. It’s rare to get a glimpse of such a well-known piece of culture emerging from the head of its creator in the moment.

After several contributions from others, he wanders off into the garden on his own to work it out and comes back with most of the song. It’s an excellent example of the ebb and flow of the individual seed of an idea, collaboration, and then individual focus again. The collaboration continues as the song arrangement takes shape and is recorded and produced by Benny. Finally ending in Sheeran on stage, alone once more.

Perfect takes a similar route, going from guitar to full orchestrated arrangement (by his brother, Matthew Sheeran) to eventually emerge as a pared back version on the album. It’s a highly effective, but very inefficient process. An entire orchestra for a day only to use a tiny bit of the recording. Always remember to kill your darlings.

One of the biggest struggles design teams have is space to focus and space to be vulnerable. The distractions of email, messaging apps and meetings in the increasingly large organisations they are embedded in creates so much noise that tuning into an emerging creative idea is difficult. The pressure to work faster, even in sprints that are intended to aid focus, isn’t always conducive to letting ideas emerge half-baked and then evolve, despite the MVP language of skateboard, scooter, bike, etc.. That language and mindset works when you’re fairly clear on what it is you’re trying to build – it’s not so useful when you’re not really sure what it is you are or should be making. I would argue that this is a key difference between design and engineering.

It’s also important to get the bad ideas out of the way. Natalie Goldberg famously talked about “letting yourself write junk” and Ernest Hemingway gave solace to all writers when he said, “I write one page of masterpiece to ninety-one pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

When Sheeran visits his old school and is talking to music students there, he makes the analogy of songwriting being like turning on a dirty tap in an old house. “You turn on the tap and it just spits out shit water for the first ten minutes”, then you start to get cleaner water with occasionally bits of grit, before the flow is clean water. When he started in earnest, he tried to write at least two-to-three songs a day, knowing that the first third of them were rubbish, but they were the necessary pathway to the good stuff. “Once all the bad songs have gone, the good songs started [sic] flowing.”

You can’t take shortcuts to the good stuff. It’s my favourite thing about writing. You can’t write a second draft without a first draft. If you try, you’ll write the first paragraph over and over for an hour and that’s not a draft. That’s just the deadly combination of perfectionist procrastination.

Who knew I would write so much about Ed Sheeran? Not me.

This post was first published in Doctor’s Note, my irregular newsletter containing a mix of longer form essays and short musing on design, innovation, culture, technology and society. You can sign up for it here.